Suffering-oriented programming

Monday, February 6, 2012

Monday, February 6, 2012 Someone asked me an interesting question the other day: "How did you justify taking such a huge risk on building Storm while working on a startup?" (Storm is a realtime computation system). I can see how from an outsider's perspective investing in such a massive project seems extremely risky for a startup. From my perspective, though, building Storm wasn't risky at all. It was challenging, but not risky.

I follow a style of development that greatly reduces the risk of big projects like Storm. I call this style "suffering-oriented programming." Suffering-oriented programming can be summarized like so: don't build technology unless you feel the pain of not having it. It applies to the big, architectural decisions as well as the smaller everyday programming decisions. Suffering-oriented programming greatly reduces risk by ensuring that you're always working on something important, and it ensures that you are well-versed in a problem space before attempting a large investment.

I have a mantra for suffering-oriented programming: "First make it possible. Then make it beautiful. Then make it fast."

First make it possible

When encountering a problem domain with which you're unfamiliar, it's a mistake to try to build a "general" or "extensible" solution right off the bat. You just don't understand the problem domain well enough to anticipate what your needs will be in the future. You'll make things generic that needn't be, adding complexity and wasting time.

It's better to just "hack things out" and be very direct about solving the problems you have at hand. This allows you to get done what you need to get done and avoid wasted work. As you're hacking things out, you'll learn more and more about the intricacies of the problem space.

The "make it possible" phase for Storm was one year of hacking out a stream processing system using queues and workers. We learned about guaranteeing data processing using an "ack" protocol. We learned to scale our realtime computations with clusters of queues and workers. We learned that sometimes you need to partition a message stream in different ways, sometimes randomly and sometimes using a hash/mod technique that makes sure the same entity always goes to the same worker.

We didn't even know we were in the "make it possible" phase. We were just focused on building our products. The pain of the queues and workers system became acute very quickly though. Scaling the queues and workers system was tedious, and the fault-tolerance was nowhere near what we wanted. It was evident that the queues and workers paradigm was not at the right level of abstraction, as most of our code had to do with routing messages and serialization and not the actual business logic we cared about.

At the same time, developing our product drove us to discover new use cases in the "realtime computation" problem space. We built a feature for our product that would compute the reach of a URL on Twitter. Reach is the number of unique people exposed to a URL on Twitter. It's a difficult computation that can require hundreds of database calls and tens of millions of impressions to distinct just for one computation. Our original implementation that ran on a single machine would take over a minute for hard URLs, and it was clear that we needed a distributed system of some sort to parallelize the computation to make it fast.

One of the key realizations that sparked Storm was that the "reach problem" and the "stream processing" problem could be unified by a simple abstraction.

Then make it beautiful

You develop a "map" of the problem space as you explore it by hacking things out. Over time, you acquire more and more use cases within the problem domain and develop a deep understanding of the intricacies of building these systems. This deep understanding can guide the creation of "beautiful" technology to replace your existing systems, alleviate your suffering, and enable new systems/features that were too hard to build before.

The key to developing the "beautiful" solution is figuring out the simplest set of abstractions that solve the concrete use cases you already have. It's a mistake to try to anticipate use cases you don't actually have or else you'll end up overengineering your solution. As a rule of thumb, the bigger the investment you're trying to make, the deeper you need to understand the problem domain and the more diverse your use cases need to be. Otherwise you risk the second-system effect.

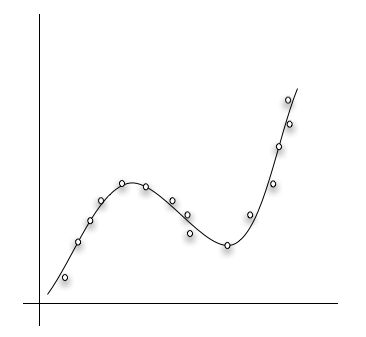

"Making it beautiful" is where you use your design and abstraction skills to distill the problem space into simple abstractions that can be composed together. I view the development of beautiful abstractions as similar to statistical regression: you have a set of points on a graph (your use cases) and you're looking for the simplest curve that fits those points (a set of abstractions).

The more use cases you have, the better you'll be able to find the right curve to fit those points. If you don't have enough points, you're likely to either overfit or underfit the graph, leading to wasted work and overengineering.

A big part of making it beautiful is understanding the performance and resource characteristics of the problem space. This is one of the intricacies you learn in the "making it possible" phase, and you should take advantage of that learning when designing your beautiful solution.

With Storm, I distilled the realtime computation problem domain into a small set of abstractions: streams, spouts, bolts, and topologies. I devised a new algorithm for guaranteeing data processing that eliminated the need for intermediate message brokers, the part of our system that caused the most complexity and suffering. That both stream processing and reach, two very different problems on the surface, mapped so elegantly to Storm was a strong indicator that I was onto something big.

I took additional steps to acquire more use cases for Storm and validate my designs. I canvassed other engineers to learn about the particulars of the realtime problems they were dealing with. I didn't just ask people I knew. I also tweeted out that I was working on a new realtime system and wanted to learn about other people's use cases. This led to a lot of interesting discussions that educated me more on the problem domain and validated my design ideas.

Then make it fast

Once you've built out your beautiful design, you can safely invest time in profiling and optimization. Doing optimization too early will just waste time, because you still might rethink the design. This is called premature optimization.

"Making it fast" isn't about the high level performance characteristics of a system. The understanding of those issues should have been acquired in the "make it possible" phase and designed for in the "make it beautiful" phase. "Making it fast" is about micro-optimizations and tightening up the code to be more resource efficient. So you might worry about things like asymptotic complexity in the "make it beautiful" phase and focus on the constant-time factors in the "make it fast" phase.

Rinse and repeat

Suffering-oriented programming is a continuous process. The beautiful systems you build give you new capabilities, which allow you to "make it possible" in new and deeper areas of the problem space. This feeds learning back to the technology. You often have to tweak or add to the abstractions you've already come up with to handle more and more use cases.

Storm has gone through many iterations like this. When we first started using Storm, we discovered that we needed the capability to emit multiple, independent streams from a single component. We discovered that the addition of a special kind of stream called the "direct stream" would allow Storm to process batches of tuples as a concrete unit. Recently I developed "transactional topologies" which go beyond Storm's at-least-once processing guarantee and allow exactly-once messaging semantics to be achieved for nearly arbitrary realtime computation.

By its nature, hacking things out in a problem domain you don't understand so well and constantly iterating can lead to some sloppy code. The most important characteristic of a suffering-oriented programmer is a relentless focus on refactoring. This is critical to prevent accidental complexity from sabotaging the codebase.

Conclusion

Use cases are everything in suffering-oriented programming. They're worth their weight in gold. The only way to acquire use cases is through gaining experience through hacking.

There's a certain evolution most programmers go through. You start off struggling to get things to work and have absolutely no structure to your code. Code is sloppy and copy/pasting is prevalent. Eventually you learn about the benefits of structured programming and sharing logic as much as possible. Then you learn about making generic abstractions and using encapsulation to make it easier to reason about systems. Then you become obsessed with making all your code generic, with making things extensible to future-proof your programs.

Suffering-oriented programming rejects that you can effectively anticipate needs you don't currently have. It recognizes that attempts to make things generic without a deep understanding of the problem domain will lead to complexity and waste. Designs must always be driven by real, tangible use cases.

You should follow me on Twitter here.

Reader Comments